Lasker Jury Chair Joseph Goldstein explores questions such as whether knowledge or imagination is more important in the creative process. Opening remarks from 2015 Lasker Awards ceremony.

Lasker Jury Chair Joseph Goldstein explores questions such as whether knowledge or imagination is more important in the creative process. Opening remarks from 2015 Lasker Awards ceremony.

A well-hung horse: Sired by knowledge and imagination

For more than a century, historians of science have been spinning a philosophical roulette wheel, pondering which is more important in the creative process — imagination or knowledge. The opening salvo in the debate goes back to the Dutch chemist Jacobus van’t Hoff, who was awarded the first Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1901. van’t Hoff is credited with two original achievements. The first is his proposal that atoms in a molecule are arranged in a three-dimensional space — a hypothesis that led to the discovery of the asymmetrical carbon atom and to the founding of a new field of physical chemistry. And the second is that the speed of a chemical reaction is related to temperature and the concentration of components. Thus, two fundamental concepts — molecular shape and reaction kinetics — originated with this one individual.

Although van’t Hoff was the first to emphasize the value of imagination in science, it was Albert Einstein who put imagination on the philosophical map. In a 1929 interview in The Saturday Evening Post, a journalist asked Einstein “How do you account for your discoveries? Through intuition or inspiration?” Einstein replied: “Both. I’m enough of an artist to draw freely on my imagination, which I think is more important than knowledge.” He explained that knowledge is limited to what we already know and understand, while imagination leads to all there ever will be to know and understand.

Einstein and van’t Hoff were exceptional rarefied thinkers who viewed imagination and knowledge as horses of a different color. To them, imagination was the domain of scientists and artists; knowledge was for curators and accountants. In Einstein’s universe, there was neither space nor time for the most imaginative of accountants — even those who could cook the books and never get caught. In the real world of today, the most creative scientists possess a special knack for asking the right question, framed in the context of existing knowledge, which is then used as a stepping-stone to imaginative thinking.

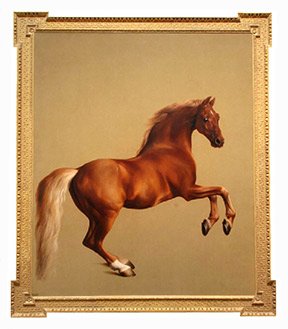

Figure 1. Whistlejacket by George Stubbs, 1762. Oil on canvas. 9.5 x 8 ft. Exhibited in Room 34 of the National Gallery of London.

A wonderful example of the creative blending of knowledge and imagination is illustrated by a portrait in Room 34 of the National Gallery in London. Room 34 contains famous 18th century British society portraits by Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds, who painted their aristocratic subjects on a grand scale in the European manner. But the portrait that I will tell you about is not one of a famous English nobleman; rather it’s a horse of a different color — in fact, it’s actually a portrait of a horse — a real Arabian horse named Whistlejacket, the star racehorse of his day in 18th century England (Fig. 1). Whistlejacket was named after a popular cocktail containing gin and molasses that was golden-colored like Whistlejacket’s flanks.

Whistlejacket: A historic painting by George Stubbs

The oil-on-canvas painting of Whistlejacket was completed in 1762 by the British artist George Stubbs. Whistlejacket is monumental in size — 9.5 ft by 8 ft — the size of an actual horse. There are 2300 paintings in the National Gallery’s collection, which includes famous works by Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Rubens, Velasquez, Van Gogh, and Cezanne. In terms of viewer popularity and museum shop sales, Whistlejacket is the National Gallery’s equivalent of The Louvre’s Mona Lisa. The National’s museum shop sells 32 different Whistlejacket-designed items, including the usual postcards, posters, scarfs, etc. But one item is unique for a museum shop — a bottle of Sloe Gin, a modern-day recreation of the 18th century Whistlejacket cocktail containing 27% alcohol.

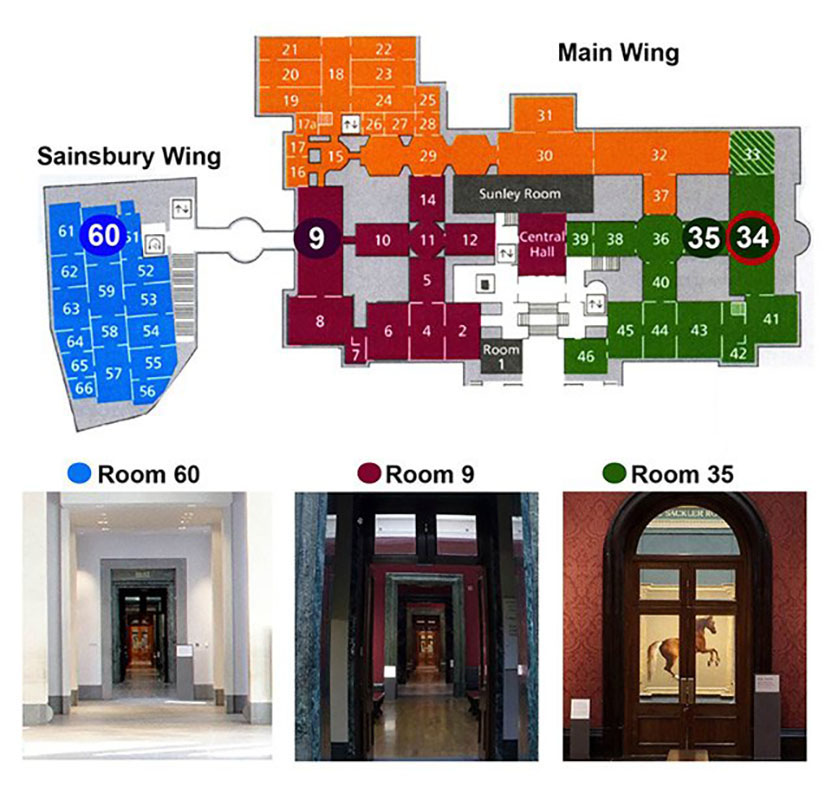

Whistlejacket occupies pride of place in its location in the National Gallery. It is hung in Room 34 at one end of the Gallery’s long main corridor in such a way that the museum-goer sees an enormous horse through multiple glass doorways as he or she wanders through 10 intervening rooms that connect one end of the Gallery to the other (Fig. 2). The painting is a true traffic-stopper and a powerful magnet, attracting and pulling people to it from remote parts of the museum. As a museum curator might say, Whistlejacket is a well-hung horse!

Figure 2. Floor plan of London’s National Gallery, illustrating the long main corridor that extends from Room 60 in the Sainsbury Wing (left) to Room 34 in the main wing (right). Whistlejacket hangs in Room 34 and can be seen through ten intervening rooms that connect one end of the museum’s long corridor (Room 60) to the opposite end (Room 34).

So what makes Whistlejacket such a remarkable painting? The answer lies in the creativity of George Stubbs, whose deep knowledge of the anatomy of horses stimulated his imagination in a unique way. Stubbs began his career as a scientist, studying human anatomy at a medical school where he also taught himself to draw and paint. His first job in 1750 was to illustrate an anatomy book on human fetal development. He then switched his anatomical interests from humans to horses.

The Anatomy of a Horse: A scientific masterpiece by George Stubbs

For the next two years, Stubbs carried out grueling dissections and experimentations on dead horses. To familiarize himself with the animal’s anatomy and physiology, he suspended the dead horses from his stable roof, stripped away their muscles, injected their veins with wax, and positioned them in various poses so that he could make meticulous drawings and engravings.

Stubbs’ studies of equine musculature and skeletal structure were published in 1766 in a graphic masterpiece, The Anatomy of the Horse. The horse is presented in 36 large plates and 18 tables with depictions of the skeleton alone, all the muscle layers, the ligaments, nerves, veins, glands, and cartilages. Stubbs’ equine drawings are memorable for their life-like quality and exceptional anatomical precision — on a par with Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings of the human body.

Stubbs’ portrait of Whistlejacket is a milestone in art history, making a radical break with convention and representing a prime example of the blending of knowledge with imagination. This was the first time that an animal was painted on a scale reserved for a king. Unlike previous paintings involving horses, Whistlejacket is depicted alone with no people, no landscape, no battlefields, no saddles, no bridles, no whips — just one horse that is free to gallop in empty space with no noisy distractions. The only areas in the canvas where space is suggested are the two small shadows cast by the rear hooves. Stubbs’ innovative use of empty space as a background focuses our attention on the subject’s individuality — his flying mane, his shiny golden flanks, his taut muscles, and his terrified eye looking at us. Why is Whistlejacket so terrified?

When the portrait was nearly finished, an extraordinary event occurred. After Stubbs had removed the canvas from the easel and placed it against the stable wall, the portrait was glimpsed by the real Whistlejacket. The real Whistlejacket so believed that he was confronting a raging stallion that he began “to stare and look wildly at the picture, endeavoring to get at it to fight and kick it.” This must surely have been the moment when Stubbs realized that he had created a masterpiece of realism — one that was recognized by his living subject.

Although George Stubbs painted Whistlejacket 250 years ago, he and his work are a reminder of a famous line by William Faulkner: “The past is never dead. It is not even past.”

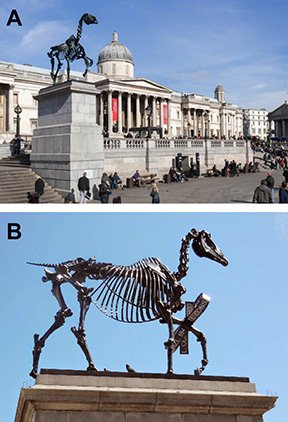

Figure 3. Haacke’s Contemporary Bronze Sculpture for the Fourth Plinth of Trafalgar Square. (A) View of the north side of Trafalgar Square, showing (from left to right) the Fourth Plinth and the National Gallery. (B) Gift Horse by Hans Haacke. 2015. Bronze. Height, 15 ft. Exhibited on the Fourth Plinth in London, 2015-2017. The tied ribbon on the right front leg of the horse skeleton displays a ticker-tape transmitting live electronic data from the London Stock Exchange.

Gift Horse: A contemporary sculpture inspired by Whistlejacket

The most recent reminder of George Stubbs’ past is a contemporary sculpture of a strutting horse that was just recently installed on top of the Fourth Plinth in London’s Trafalgar Square, situated just in front of The National Gallery where Whistlejacket hangs (Fig. 3a). The new equine sculpture was created by Hans Haacke, a 78-year-old German-born artist who has lived in the United States for the last 50 years. Haacke is one of the fathers of Conceptual Art whose followers make minimalist sculptures from industrial materials and found objects. Most recently, Haacke has led a new art movement called Institutional Critique in which artists use their art to draw attention to hidden connections between politics, business, and established organizations such as museums and churches.

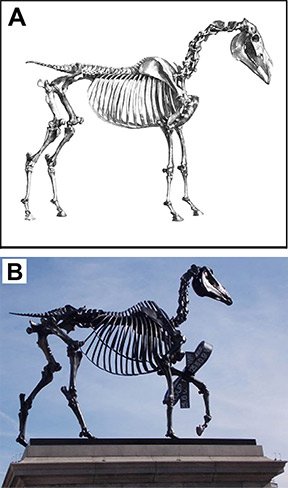

Haacke’s new bronze sculpture is 15 feet tall, twice the size of a real horse, and weighs 4000 pounds (Fig. 3b). It is attracting wide public attention — not because it is a horse of enormous size, but because it is a skeletal sculpture of a horse (Fig. 4). The sculpture was inspired by George Stubbs’ Whistlejacket painting and is based on one of the skeletal drawings in Stubbs’ classic book The Anatomy of the Horse. Haacke titled his bronze skeleton Gift Horse. Apropos of its name, one of the skeleton’s front legs is wrapped with a large ribbon tied in a pretty bow like on a present. The ribbon displays a ticker-tape transmitting live electronic data from the London Stock Exchange. Why would Haacke decorate a dead horse from the 18th century with live stock quotes from the 21st century?

The answer lies in Haacke’s knowledge of the historical background of Trafalgar Square combined with his imagination in using art as a platform to comment on established institutions. The Square’s name commemorates the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar, Britain’s spectacular naval victory over France during the Napoleonic Wars. At the center of the Square stands a tall column on top of which sits a statue of Lord Horatio Nelson, England’s greatest naval hero, who was killed at Trafalgar. Surrounding the Nelson Column are four large stone pedestals, which the British call the Four Plinths. Three of the plinths bear equestrian sculptures of Kings or military heroes.

The Fourth Plinth, erected in 1841, was intended to display a stature of King George IV on horseback, but the cost was so exorbitant that it was never completed, and it remained bare for 150 years until the British government decided to use it as a public platform for displaying a contemporary sculpture that could be viewed by the 40,000 people who visit Trafalgar Square each day. Every 1 to 2 years, 100 leading artists from around the world are invited to enter a competition. Since 1999, ten artists have been selected to showcase their artwork on the Fourth Plinth.

Figure 4. How Stubbs’ Anatomical Horse Drawings Inspired Haacke’s Bronze Sculpture. (a) George Stubbs, First Skeleton Table, 1766. Copper plate drawing. (McCunn, J.C. and Ottaway, C.W. The Anatomy of the Horse by George Stubbs. 1976. Dover Publications, Inc.). (b) Hans Haacke,Gift Horse. 2015.

Combining knowledge and imagination to create Gift Horse

Hans Haacke’s Gift Horse is arguably the most deeply researched of all the sculptures to have appeared on the Fourth Plinth. It is steeped in art history, reaching back to the anatomical work of George Stubbs. There is also the historical connection to the British and their passionate love for horses, which raises the question as to why Haacke would sculpt the skeleton of a horse rather than the real thing. I think he is teasing the British, reminding them of the precariousness of their empire and of their poor financial situation 150 years ago, which left the Fourth Plinth empty and bare. And now Haacke, a German-American, has come to the rescue — not with a sculpture of a real horse — but with the bare bones of King George’s horse.

There is also a political bite to Gift Horse. The ticker-tape on the skeleton’s leg is a reminder that money is the power that drives both the good and the bad in the world and the dynamic behind modern-day income inequality. Then there is the provocative title of Gift Horse. It is almost certainly an allusion to the Greeks’ Trojan Horse that led to the saying “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts.” Is Haacke telling us to “Beware of brokers bearing hot tips?” Or is he warning the pound-conscious British to “Beware of Greeks bearing Euros?”

2015 Lasker Awards: A marriage of knowledge and imagination

George Stubbs and Hans Haacke achieved greatness by a similar route: both used existing knowledge as a stepping stone to imagination. After lunch, you will hear how this year’s Lasker Awardees blended knowledge and imagination to create something new. In much the way that Stubbs redefined portraiture by imaginative choice of subject matter and innovative elimination of background noise, so today’s medical research laureates have produced original portraiture that distinctly and explicitly illustrates how our cells respond to DNA damage and how our immune system deploys a powerful strategy to fight cancer.

In much the same way that Haacke’s knowledge of complex contemporary social and financial systems stimulated him to expose those things in the world that need to be brought to attention, so today’s public service awardee honors an organization renowned for its bold and innovative leadership in health emergencies — as recently exemplified by its frontline response to last year’s Ebola crisis.