Normal science, in Kuhn’s view, is essentially a mopping-up operation. This view would not be popular with the Geneva high-energy physicists who believe that their discovery of the Higgs particle is paradigm-shifting — even though, in the Kuhnian sense, it is a prime example of normal science operating within the existing paradigm of the Standard Model of particle physics. Had no Higgs been found, this would have been a paradigm-shifting anomaly worthy of a media celebration — not one showing the highfalutin Geneva physicists hugging each other, but one showing them tossing their mops and licking their chops.

Kuhn’s own paradigm shift

Speaking of anomalies, there are several that surround Thomas Kuhn himself. Ironically, he produced his own paradigm shift by debunking the prevailing paradigm of scientific advancement. How did a scientist who was passed over for tenure at Harvard write one of the great books of the last 50 years? Since its publication in 1962, Structure has sold 1.5 million copies in 16 languages, is still required reading in courses in the philosophy of science, and is cited more often than the classic works of Sigmund Freud, Noam Chomsky, and James Watson. Its success is even more surprising when one takes a look at Structure’s first review published in Scientific American in 1962. The last sentence reads: “It is much ado about very little.” Such skepticism is the true test of a paradigm shift.

Structure was a success because of the clever way in which Kuhn summarized his theory with two sexy catchwords. In the last 10 years, paradigms have pervaded every aspect of our culture. Today, you can purchase audio and video equipment from Paradigm Electronics in Canada; you can buy bonds and stocks from Paradigm Financial Partners in the UK; you can solve your human resource problems from Paradigm Shift Consulting Service, Ltd. in India; and — most provocative of all — you can read a Paul Krugman op-ed piece in The New York Times entitled “The Ponzi Paradigm.”

To biologists, it is puzzling that Kuhn failed to mention the two greatest paradigm shifts in the biological sciences — Darwinism and Mendelism. The most likely explanation is that Kuhn was totally focused on physics, which in the 1950s and 1960s was top scientific dog.

It is ironic that the year in which Structure appeared — 1962 — was the same year in which Nobel Prizes were awarded to the scientists who obtained first molecular structures of DNA and protein — to Watson and Crick in Physiology or Medicine and Perutz and Kendrew in Chemistry. If ever a scientific field were on the verge of a paradigm shift, it was biology in 1962. The genetic code had just been cracked by Nirenberg, and recombinant DNA and gene cloning were just around the corner. To paraphrase Virginia Woolf, “On or about December 10, 1962, the world of biology changed.”

Paradigm rifts and tiffs in the arts

What was Kuhn’s view on paradigm shifts in the arts? He believed that great works of art retain their value throughout time even in the face of revolutionary changes in style. To quote Kuhn, “Picasso’s success has not relegated Rembrandt’s paintings to the storage vaults of art museums” (2). So what should we call Picasso’s and Braque’s transition from impressionism to cubism or Jackson Pollock’s and Willem de Kooning’s transition from realism to abstract expressionism? If they’re not paradigm shifts, given the cutthroat competitive nature of the art world, what about paradigm rifts? Or paradigm tiffs?

James Rosenquist and instantly forming ideas

Although Kuhn’s paradigm model may not be strictly relevant to the arts, it is the artists who have shed light on a key question never answered by Kuhn: Where do the daring ideas in science that bring on paradigm shifts come from? Some ideas, according to the American artist James Rosenquist, arise explosively in a light-bulb moment in the middle of the night. Rosenquist is one of our most creative contemporary artists. Together with Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, he was one of the three founding members of the Pop Art movement in the 1960s. One of his signature paintings of 1960, entitled President-Elect, a charismatic President John F. Kennedy is shown juxtaposed with a woman’s hand holding a piece of devil’s food cake and a 1960 Pontiac. The devil’s food cake is a stand-in for a tempting female, and the car is prophetic, foreshadowing by three years JFK’s death in a motorcade.

Now that Rosenquist is approaching 80 years of age, his artistic paradigm has shifted — from visualizing popular culture to visualizing the philosophy of ideas. According to Rosenquist, “A good idea that spurs you on to do something should have pictorial power. After all, what does a great idea look like?” (3).

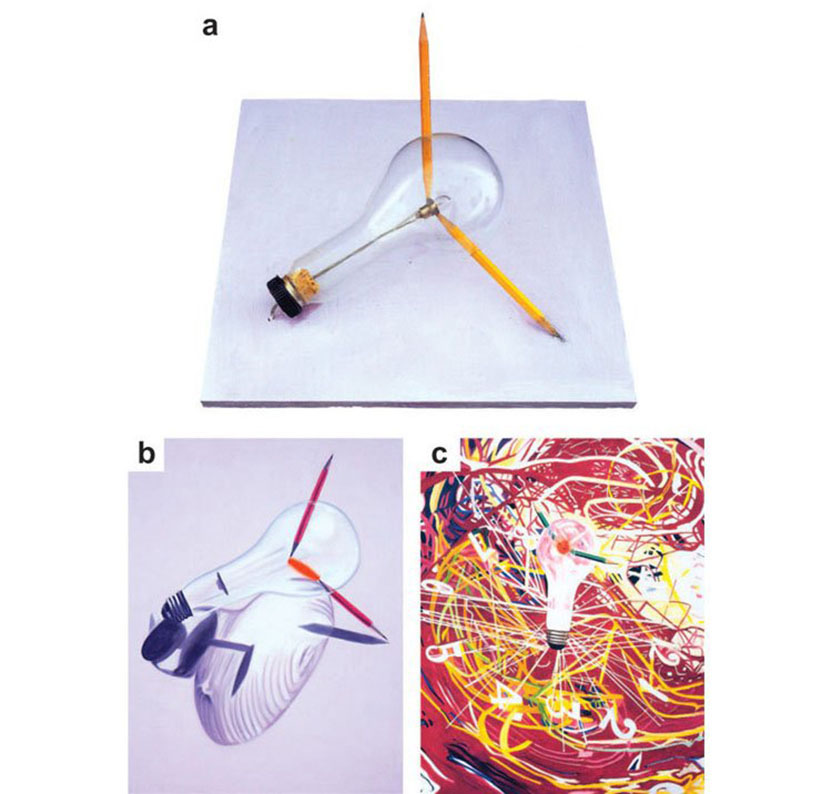

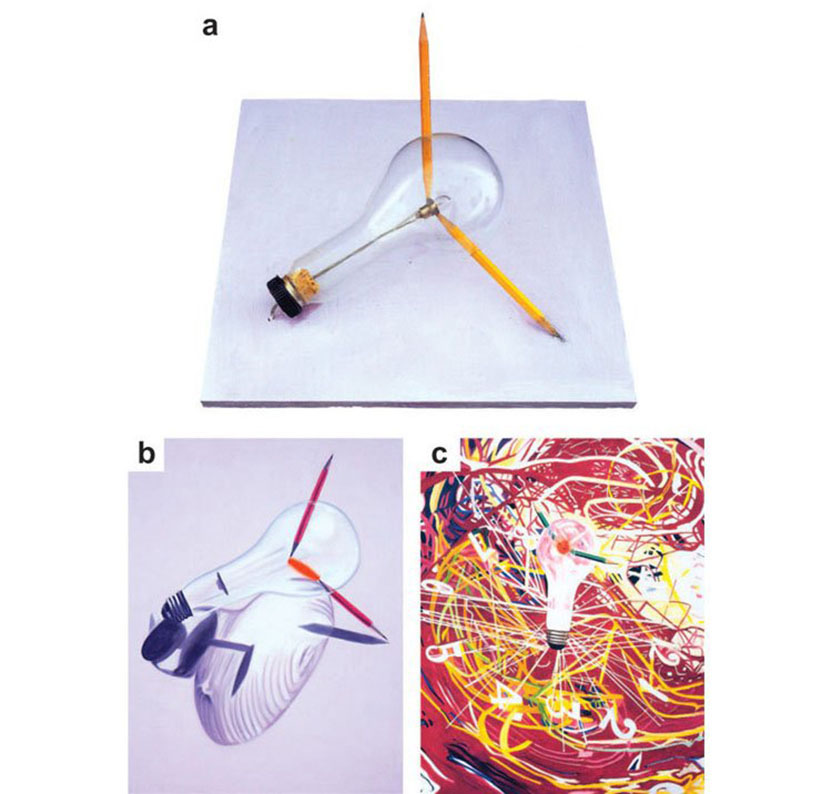

So in 2007, Rosenquist created a series of sculptures and paintings that deal with the origin of ideas (3). Fig. 1a shows a sculpture entitled Idea in Middle of the Night. The pencils that pierce the light bulb symbolize the hands of a clock and the writing down of an idea that pops into your head in the middle of the night. Fig. 1b shows a painting entitled Idea, 2:50 A.M. The bulb is the light that goes off suddenly in your mind in the wee hours of the night like an intellectual alarm clock. The bulb is also the light that you need to write down your fleeting inspiration before it fades away.

In the painting of Fig. 1c, entitled Idea 3:50 A.M., the light bulb represents the beginning of an idea that explodes in so many different directions that it becomes an abstract version of itself and ultimately develops into something completely new — like a paradigm shift.

Figure 1. Instantly forming ideas. James Rosenquist. 2007 (a) Idea—Middle of the Night. Light bulb, pencil, and electric wiring on painted wood. 7 1/2 x 12 x 12 inches. (b) Idea—2:50 A.M. Oil on canvas. 57 x 44 inches. (c) Idea—3:50 A.M. Oil on canvas. 63 x 49 inches. Exhibited at Acquavella Gallery, New York, NY.

Giuseppe Penone and slowly forming ideas

Not all artists agree that a great idea arises in an explosive moment. The Italian sculptor Giuseppe Penone tells us that a great idea forms in a very slow and gradual process of aggregation and crystallization, such as that which occurs in the formation of a rock.

Penone is widely regarded as one of Italy’s leading contemporary artists. He is best known for his outside environmental installations in which trees sculpted out of wood or bronze are integrated with nature in a thematic way. Penone’s most recent installation was commissioned as the centerpiece for this year’s Documenta exhibition of contemporary art, which takes place every five years in Kassel, Germany (4).

Figure 2. Slowly forming ideas. Giuseppe Penone. 2012. Bronze and granite stone. 30 x 10.8 feet. Idee di pietra (Ideas of Stone). Exhibited at Karlsaue Park, Documenta 13, Kassel, Germany.

Of the two different ideas for the origin of ideas, Rosenquist’s dream theory of the eureka moment is more apocryphal than real. Perhaps the most famous example in science is August Kekule’s somnolent vision of a snake biting its tail, which supposedly revealed to the German chemist the true structure of the benzene ring.

But the dream vision most relevant to biomedical science occurred to the German physician, Otto Loewi, who won a Nobel Prize in 1936 for his discovery of acetylcholine as a neurotransmitter. Before Loewi’s light-bulb moment, it was unclear whether signaling across a synapse was electrical or chemical in origin. Loewi’s dream-inspired experiment, done within hours after he awoke, provoked him to rush to his lab and remove the beating hearts from two frogs. In the first heart, he left the vagus nerve attached, and in the second heart he removed the vagus. Both hearts were then placed in separate salt solutions. When Loewi stimulated the vagus nerve of the first heart, it beat slower. Then, when he took the fluid from this stimulated heart and added it to the second heart that had no vagus, the second heart now beat slower, proving that a soluble chemical was released from the vagus nerve and it controlled the heart rate. The chemical turned out to be acetylcholine.

Did the shy and reserved Otto Loewi tell his tale as it really happened? Everyone expects tall tales from certain Texas Nobel laureates, but not from a taciturn German one.

After lunch, you will hear presentations describing the discoveries of this year’s Lasker winners. The daring ideas that led to their awards were formed in a complex way that combines the slow-hunches of Penone with the instant light-bulb moments of Rosenquist. And now it’s time to enjoy your lunch — in instant Rosenquist fashion.

References

Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions: 50th Anniversary Edition. 4th edition. (University of Chicago Press, 2012).

Kuhn, T.S. The Essential Tension. (University of Chicago Press, 1977) p. 345.

Bancroft, S. James Rosenquist: Time Blades. (Acquavella Contemporary Art, Inc., 2007).

Mangini, E (2010). Giuseppe Penone talks about Idee di pietra (Ideas of Stone). Artforum International. 49, 226-229.

More Jury Chair Essays

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of a highly influential book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, by the physicist Thomas Kuhn (1). This book introduced the world to “paradigms” and “paradigm shifts” — two of the most misused, overused, and abused words in the world today.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of a highly influential book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, by the physicist Thomas Kuhn (1). This book introduced the world to “paradigms” and “paradigm shifts” — two of the most misused, overused, and abused words in the world today.